sustainable luxury:

when opulence is good for the planet

Sustainable luxury has become a term that is deeply rooted in controversy. How can luxury, a lifestyle often associated with opulence and excess, be sustainable?

This controversy appears to arise from the definition of luxury itself, and its subsequent juxtaposition with the tenants of sustainability. While sustainability proves to also be a difficult term to define, most sources agree that the tenants of social, economic, and environmental impacts are important pieces to consider in this multi-faceted and multi-disciplinary movement. In the same way, luxury can also carry a variety of different meanings.

Some sources claim that luxury is the abrasive and excessive utilization of resources for the benefit of the select few or elite. This definition, if considering aspects of sustainability, not only violates social and economic aspects of sustainability (separation of the elite; frivolous spending of an elite class), but also violates environmental aspects (over-consumption of natural resources). A basic understanding and initial impression of luxury would appear to confirm this definition as absolute.

Traditionally speaking, luxury “has been associated with exclusivity, status, and quality” (Lowe as reported by Atwal and Williams, 2009). In addition, luxury’s Latin root (“luxus”) and historical connotations have plagued luxury with negative sentiments, including a correlation between desire and sin (Lowe). However, upon further review, it appears that perhaps the general understanding of luxury is only being viewed at the surface level, and that the two terms (sustainability and luxury) can, in fact, be considered together as one unit

Kapferer’s 2010 article presents enlightening new perspectives on luxury and its potential and current classification as a sustainable practice. Quality, durability, and no-delocalization principles can push luxury industries towards sustainability.

The article makes a clear distinction between the luxury industry and the faux luxury portrayed by the fashion industry, which is often a part of or akin to mass-market production. This idea is discussed in other articles, but is summarized nicely by Kapferer, when he states: “durability is the enemy of the fashion industry and of the mass market industry” (Kapferer, 2010).

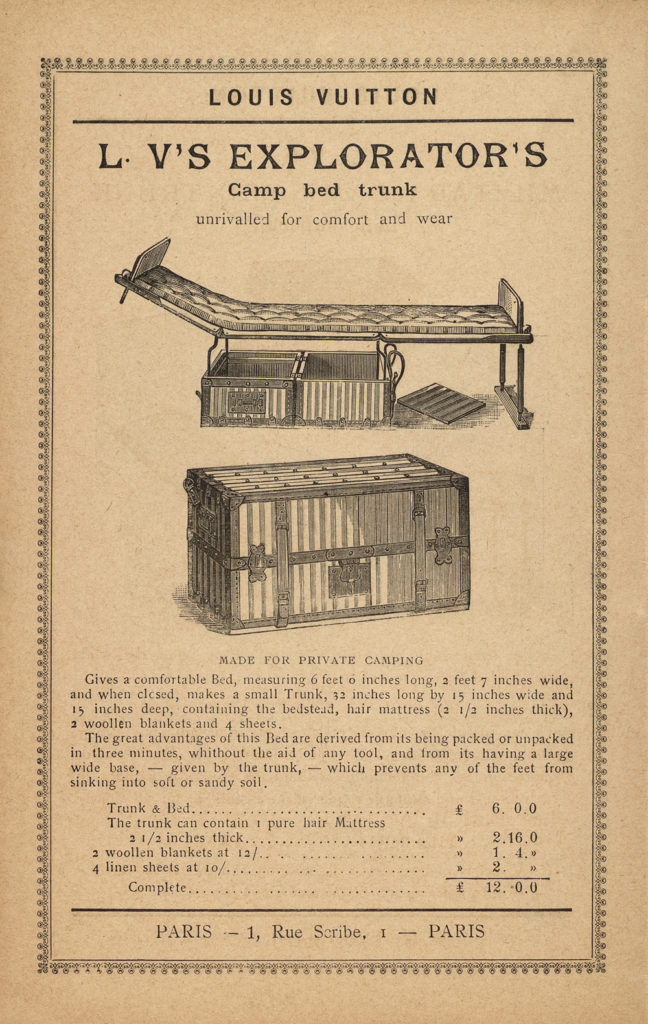

Although more expensive, merchandise from companies like Louis Vuitton are exceedingly durable and offer after-sales care and maintenance. Like Louis Vuitton, “ninety percent of all Porches produced are still being driven” and “Maranello mechanics will work on any old Ferrari, whatever its age”. “Luxury is the business of lasting worth”, and this durability and subsequent reduction of a widespread “throw-away-society” can be found at the “heart of sustainability” (Kapferer, 2010).

In this same article, the no-delocalization principle of luxury is of prime importance when viewed in the context of sustainability. While a significant portion of the fashion industry and mass-market producers opt for exporting their labor, luxury industries focus on their historical and legacy craftsmanship, most times refusing to outsource their product.

By licensing their brands, fashion and mass-market producers lose more and more control over their brand abroad, and thereby lose more and more control on the labor and manufacturing conditions. The article cites Nike as a major culprit in this case, as its outsourcing has notoriously led to sweatshop conditions in other countries. This uncertainty of labor conditions has negatively affected the company’s reputation and other companies who outsource their products.

This unbridled outsourcing and lack of transparency has generally led to distrust among consumers. However, luxury companies such as Chanel produce their goods in-house in the Chanel factory, and do not outsource their product. The article sums this up very clearly by stating: “real luxury is not aimed at cost reduction, but at the creation of value, through rare and unique singularities, like no-delocalization”.

The emphasis on craftsmanship versus the exploitation of unskilled labor is another entity that sets luxury goods apart. In this light, luxury is not necessarily viewed as an unsustainable indulgence that creates and portrays social rifts through displays of excessive opulence, but instead could be viewed as a safeguard that can eliminate the very exploitation of lower social classes through integrated fair labor practices. In this way, luxury can be viewed as a sustainable practice: socially, economically, and environmentally.

Quality, durability, and no-delocalization principles can push luxury industries towards sustainability.

Lowe documents the historical progression and evolving definition of the term “luxury”. As previously mentioned, luxury has been historically associated with desire, over-indulgence, and sin. In the 18th century, “the belief that luxury was ‘dangerous’ shifted, and the association between luxury and desire was placed in a more innocuous light” (Lowe, 2010).

This definition was most notably changed at the turn of the century, when mass market and the expedited production abilities of industries provided cheap luxuries to the masses.

In an attempt to gratify the innate and insatiable desire to join increasing social status, even if it were beyond their means, “cheap luxuries” were offered to the public to offer a sort of faux sense of elitism.

“While the rich and affluent may consume luxury goods to assert status and membership to the elite class, the modest may consume the same goods to gain status, but with purely conspicuous intention” (Lowe, 2010 as reported by Truong et al., 2008).

This “keeping up with the Jones’s” mentality has resulted in individuals indulging in expenditures that may be beyond their means, even just for experiencing such increased status for a limited amount of time. Obviously, this practice is not sustainable economically, by any means.

Lowe appears to point to this aspect as one of the bubbling problems behind luxury as a sustainable practice, as the “faux luxury” industries that cater to the masses may not be as sustainable in their practices as counterpart “true luxury” industries.

Kapferer makes this distinction, stating that despite an ongoing critique of luxury, mass consumption growth is the reason why resources will be scarcer (i.e. higher demand for mass air travel, “not the private jets”). A distinction between such luxury types is suggested to be vitally important when discussing the topic of sustainable luxury.

“In an attempt to gratify the innate and insatiable desire to join increasing social status, even if it were beyond their means, ‘cheap luxuries’ were offered to the public to offer a sort of faux sense of elitism.”

Moscardo and Benckendorff have a very different take on sustainable luxury. Their paper focuses not on what sustainable luxury is currently doing, but what it may do in the future.

Eco-toursim is pointed to as a potential new form of sustainable luxury. “In the modern area, many destinations have become popular for mass tourism after being initially a place of interest for elites looking for fashionable luxury experiences [sic]” (Moscardo and Menckendorff).

Essentially, as more individuals and different societal classes vacation to luxurious resorts and locations (even sometimes beyond their means), elite classes may be pushed to more remote areas, as they search for more remote and pristine destinations (i.e. Africa and Australia).

On one hand, this practice could open up opportunities for sustainable, small-impact eco-tourism. However, on the other, it could destroy these pristine areas from increased traffic and overuse.

This document also mentions the academically popular distinction between the “democratization of luxury” among the masses – which is driven “by a desire for social status through conspicuous consumption” – and the more refined luxury of the elite class – which is “now more concerned about experience, authenticity, and rarity of goods and service than conspicuous consumption” (Moscardo and Benckendorff as reported by Husic and Cicic, 2009; Poblete, 2008).

Organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund believe that luxury eco-tourism opportunities can incorporate sustainable practices with an authentic experience. “A report for the World Wildlife Fund argues that luxury brands can improve their ecological and social sustainability considerably by changing a number of design, production, and management approaches” (Moscardo and Benckendorff as reported by Bendell and Kleanthous, 2007).

However, Moscardo and Benckendorff argue that such opportunities are lacking, and find little evidence of this shift or seeking of these aforementioned opportunities.

Eco-toursim is pointed to as a potential new form of sustainable luxury.

“Many in the business and financial communities view sustainability as a means to reduce long-term risk, enhance economic competitiveness, and promote social well-being. In Hecht et al., there appears to be an economic benefit to corporate sustainability.

Many consumers are also becoming more aware of sustainability issues and expect manufacturers to develop greener and/or safer products” (Hecht et al., 2014). We have seen examples of corporations conducting green initiatives in our previous readings, but many of them were manufactured items that were more widely available to the general public via mass production (i.e. Nestle, Campbell soup) (Kiron, 2013).

In light of the concept of sustainable luxury, however, it seems that luxury items may inherently promote some sustainable practices in the very framework of their business. As a result, perhaps a strong amount of their appeal comes from such sustainable tenants as their durability and relative absence of labor outsourcing.

In reviewing Seto et al.’s 2010 work, it appears that gentrification is a major issue that prevents true sustainability from occurring.

Sustainability has a social component. In line with the general definition of sustainability, “social change is a central element of development” and an essential component in urban sustainability (Seto et al., 2010).

In the creation of slums and gated communities, urban areas are becoming gentrified and widening the gap between classes. The favelas in Rio de Janeiro is one prime example of this social separation. As an outskirt to the city, these favela communities are socially and geographically isolated into areas of extreme poverty and poor health.

Gated and restricted access communities have become the new form of social exclusion in urban areas (Seto et al., 2010). According to this work, in order to be fully sustainable, this separation must be alleviated.

“Gated and restricted access communities have become the new form of social exclusion in urban areas (Seto et al., 2010).”

So the question is, how can sustainable luxury work, if this class separation is undesirable in the context of sustainability?

Specifically, if “true” luxury is to be sustainable, doesn’t it have to be available for all? I believe the answer lies in a revisit to the basic needs and necessities of human life.

Lowe describes luxury as the refinement of basic human needs.

In that context, if quality of human life is preserved by offering the needs of a quality existence among all social classes, can luxury have the ability to be completely sustainable?

Or will there always be something wanting – is sustainability only available in the absence of all social exclusion?

These questions pose for an interesting philosophical discussion. In reviewing all literature however, I believe that if quality of human life is preserved among all social classes, luxury can indeed have a sustainable, positive, and potentially “trickle-down” impact around the world. If considered to be merely a refinement of basic human needs, if these needs are offered in some adequate fashion to all social classes, I see no reason as to why they cannot be considered sustainable.

Ultimately, by reviewing appropriate literature, it appears that “true” luxury has a significant potential to be a sustainable practice. In fact, many companies, by the very definition of their business (and subsequent dedication to quality and durability), can already be considered sustainable.

Sustainable luxury is not the oxymoron that it appears to be on its surface layer.—-

Sources:

Hecht A., Fiksel J., & Moses M. 2014. Working toward a sustainable future. Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy 10(1) Published online Jan 15, 2014. http:///archives/vol10iss2/communityessay.hecht.html

Low, T. (2010, June). Sustainable luxury: a case of strange bedfellows?. In Tourism and Hospitality in Ireland Conference, Shannon College of Hotel Management, Ireland (pp. 14-16).

Kapferer, J. N. (2010). All that glitters is not green: The challenge of sustainable luxury. European Business Review, 40-45.

Kiron, D., Kruschwitz, N., Haanaes, K., Reeves, M., Goh, E., Diepenhorst, C., & Woods, D. (2013). The innovation bottom line. MIT Sloan Management Review Research Report Winter.

Moscardo, G., & Benckendorff, P. (2010). Sustainable luxury: oxymoron or comfortable bedfellows?. In Proceedings of Global Sustainable Tourism Conference. Global Sustainable Tourism (pp. 709-728).

Seto, K. C., Sánchez-Rodríguez, R., & Fragkias, M. (2010). The new geography of contemporary urbanization and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35, 167-194.